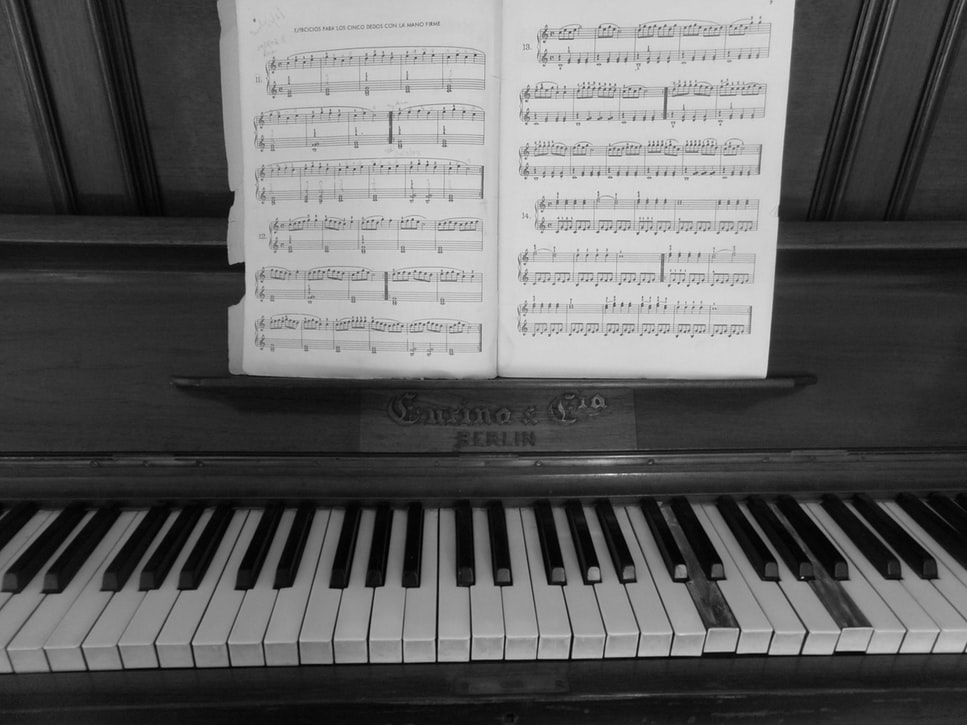

This is why Hanon exercises are a waste of time (and possibly dangerous)

Want to stir up a group of mild-mannered piano teachers? Ask them about Hanon exercises

Designed by French composer Charles Louis-Hanon, these finger exercises have been revered and reviled since they were first released in 1873 in a book titled The Virtuoso Pianist. Pianists and teachers who use Hanon claim the exercises improve three things: finger strength and independence, wrist and forearm strength, and endurance. Conversely, those pianists and teachers who reject Hanon claim that the exercises are at best useless and at worst, dangerous.

As a lifelong pianist with 26 years of teaching experience, I am a committed member of the latter group. Why? My reasons are best explained by examining the three things Hanon supporters claim the exercises improve:

Myth #1 - Finger strength and independence

Fact: Anything that moves the fingers on the keys will build finger strength and independence. The most useful and effective way to do this is to practise scales, chords, and arpeggios every day. They are the building blocks of western piano music and they are patterns that pianists encounter in repertoire every day. Hanon exercises don’t improve on them. And beyond a good regimen of scales, chords, and arpeggios? The best way to learn technique is through repertoire, not through repetitive exercises. My undergraduate professor taught me this during my first semester at university. I needed to work on left-hand finger independence. He assigned me a Chopin Etude. By the time the Etude was ready to perform, my technique had improved and I had something gorgeous to play. I’ve seen this work dozens of times in my own teaching. When a student falls in love with a piece, she’ll work like mad to perfect it. The motivation to conquer the music leads to a much more thorough technical grounding than any stand-alone exercise.

Myth #2 - Wrist and forearm strength

Fact: One of the most dangerous myths of piano playing is that it requires an enormous amount of forearm strength. In reality, the arms should be relaxed conduits of the power that comes from the pianist’s lower body. Yes, you read that correctly. If you don’t have enough power at the keyboard, check your feet. Are they firmly on the ground? Is your back straight? Are your shoulders relaxed or are they up around your ears? Make sure you’re playing from the whole body, not the forearm. The arms just carry the energy from the body to the keyboard. Focusing on forearm strength leads to tension, forearm injury, and an unmusical, aggressive tone.

Here's how to avoid tension in your playing... the correct way

Myth #3 – Endurance

Fact: Any long musical passage or composition will build endurance. Ask yourself, which would you like to play perfectly when you master it? A lovely Etude or an exercise?

True endurance means learning to be intense when you need to be, and to release where and when you can. Rote exercises encourage pianists to keep moving without taking necessary pauses. This leads to tension and injury.

In addition to these reasons, I offer one more: Hanon exercises are simply not musical. As musicians, we train the ear as much as - or more than - we train the hands. A side-effect of unmusical exercises is that we stop listening. And when we stop listening, we stop being musical. Perhaps we need to look at the reasons we’re playing the piano. Are we trying to become better technicians or are we working to beautifully recreate music we love? When we practise repertoire we long to play - accompanied by a steady diet of scales, chords and arpeggios - we’re being trained as musicians, not technicians. And isn’t this the reason we chose to become pianists?

by Rhonda Rizzo (27 June 2019)

From Pianist

沒有留言:

張貼留言